Since the rise of modern scholarship, the Christian tradition has come under attack. Virtually everything it claims and holds was brought under scrutiny; Jesus Christ is not an exemption. Thus, the quest for the real Jesus of history and Christ of faith characterized the 18th and 19th centuries scholarship. This was an attempt to recover the real Jesus as it opposes what is contained in the Bible.

But such a quest took another form with the arrival of a British Philosopher of Religion, John Hick. Hick, troubled with the problem of religious diversities, delved into discussions on how to reconcile them, as a single whole in diversities. How can Jesus be unique from the other revealers of God in other faiths? What can we know about the historical Jesus? To do this, re-interpreting the historical Jesus was inevitable for Hick. Therefore, this paper examines Hick’s pluralistic Christology by exploring his theory of religious pluralism as the basis for that reconstruction.

Conceptual Clarification of Terms:

Religious Pluralism:

To begin with, pluralism should be differentiated from plurality of religions. While the two are strongly interwoven and often difficult to be differentiated, the differences however, can be shown in this way: “plurality refers to the fact of manyness while pluralism refers to the fact and consciousness of manyness”.[ Richard J. Plantinga, Christianity and Plurality: Classic and Contemporary Readings (Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 1999), 6] Plurality of religions is the acceptance of the reality of the existence/presence of many religions. The diversity of religions in our society is what can hardly be denied. Religious pluralism on the other hand is the licensing of the plurality of religions. In other words, pluralism recognizes and appreciates the manyness of religions as equally valid and authentic means.

Much more, pluralism opposes two main views associated to plurality of religions- exclusivism and inclusivism. The former stresses the belief that Christianity is nominative, final and unique.

Traditionally, it holds that “salvation is available only through faith in God’s word and deeds in history culminating in Jesus Christ”[ T. R. Philips, “Christianity and Religions” in Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. E.d. by Walter A. Elwell (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1984), 231] (this is same to other religions). While for the Christian, the claim is clearly captured in the following expression “extra ecclesiam nulla Sallus (no salvation outside the Church). This claim explains the position of Jesus Christ in the Christian faith and arouses reactions from non-Christian worldviews.

Second to it, is termed as ‘religious inclusivism’. Like the former, it emphasises the unique role of Jesus of Christ, albeit in dissimilar terms. Philips says “inclusivism holds that God’s imminent and saving grace is available to all ages in Jesus Christ”.[ Ibid] The claim is that, all others, can access salvation and liberty provided in Jesus Christ irrespective of their faiths. Those who belong to this camp argue that, one needs not to be part of the Church to be saved. Christ is available to all. As examined above, exclusivism and inclusivism possess a form of emphasis on Christ’s uniqueness. It is against this notion that pluralism can best be understood. Religious pluralism, therefore, opposes these notions. Pluralism stands as a bridge – a bridge that allows a cross over to embracing other religions, competing views as authentic and valid.

It involves respecting the uniqueness of others, and opens room for dialogue, tolerance and openness. For instance, Evans maintains that “pluralism is the doctrine that either generally or with reference to some particular area of judgement, there is more than one basic principle”.[ J. D. G. Evans, “Cultural Relativism: The Ancient Philosophical Background” in Philosophy and Pluralism e.d. by David Archad (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986),47. ] His argument calls for acceptance of other truths other than one’s own.

Following the foregoing, one can safely say that, pluralism is a doctrine that asserts equality to all religious views. This is grounded in the basic notion that; no religion is superior to others.

Hick’s Theory of Religious Pluralism

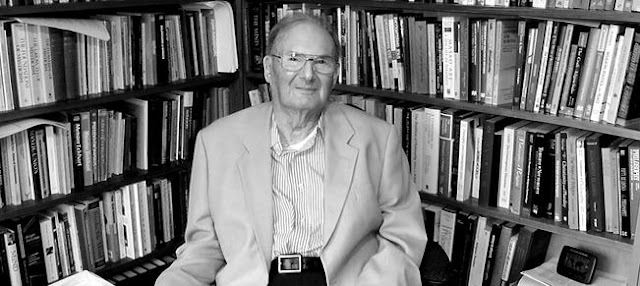

Perhaps, more than anyone in the last century, the British Philosopher of Religion, John Hick occupies a significant place for the pluralistic campaign. Born in Scarborough, Yorkshire England on 20th January, 1922, Hick was trained in the world’s most renown Universities; Edinburgh 1948, Oxford 1950 and Cambridge 1964.[ John Hick, God has Many Names (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983):13 ] His journey to Christian faith was dramatic, as the young Hick saw Christianity as lifeless and utterly a matter of infinite boredom[ David S. Nah, Christian Theology and Religious Pluralism (Cambridge: James Clarke and Co, 2012):25. ] until his conversion in his days at the Hull University. During his early Christian life, like any other conservative evangelicals, Hick believed in the traditional claims, creeds and confessions on the biblical account creation, the incarnation, and virgin birth, miracles, life after death and so on. These views Hick would later abandon for radical liberalism.

Perhaps, the beginning of this journey was his experience while at Birmingham as a Professor of Philosophy.

Given the above, Hick’s pluralistic hypothesis of religion was developed under three stages.[ Ibid] With his first publication on religious pluralism, God and the Universe of Faiths, Hick made known his position by appearing as a ‘Revolutionist’ – a revolutionist in philosophical and theological thinking. In that book, Hick called for a Copernican Revolution in Christian Theology. Here, he urged the Church to “shift from the dogma that Christianity is at the centre to the realization that is God who is at centre and that all religions including our own, serve and revolve around him”.[ John Hick, God and the Universe of Faiths (London: Macmillan, 1973):2.] For him, as Copernican revolution changed the cause of astronomy, so did he advance a theory that would change the theologico-philosophical discussion of world religions. No longer should Christians see Christ as unique and superior mediator than others.

The second stage of Hick’s pluralistic hypothesis, is to modify the former view to allow the inclusion of non-monotheistic religions. In this stage, Hick shifted his focus from theocentricism to what he termed as reality-centrism.

The reason is to respond to the criticism raised against his Copernican revolution. Olawoyin rightly observed the purpose when he notes: “Hick reinterpreted what we considered to be one of the most important beliefs in the major religions of the world - the affirmation of ultimate reality so as to reconcile the two main notions (personal/impersonal) as perceptions of the same reality”[ O. N. Olawoyin, “John Hick’s Philosophy of Religious Pluralism in the Context of Traditional Yoruba Religion” in Thought and Practice: A Journal of the Philosophical Association of Kenya (PAK) 7:2 (December, 2015):56] Hick’s intention here is to include religions he considered as post-axial religions. These religions are soteriologically oriented according to Hick.

This basic assumption led him to develop a fullest and matured stage of his religious pluralism. With his Problems of Religious Pluralism, he insists that, all religions, theistic or non-theistic are soteriological valid. Such a thesis was proposed to set a testing criteria at which the valueness of these religions can be ascertained.[ John Hick, Problems of Religious Pluralism (London: Macmillan, 1985):44. ]

Arguably, Hick’s Interpretation of Religion is the most significant treatment of religious pluralism. Throughout this work, Hick was sophisticated and systematic in interpreting world major faiths in a way it encompasses his matured Philosophy of religions.

Having grounded that, all religions are soteriological valid, Hick went on to state his hypothesis.

I want to explore the pluralistic hypothesis that the great world faiths embody differently perceptions and conceptions of, and corresponding different Reponses to, the Real from within the major variant ways of being human; and that within each of them the transformation of human existence from self-centeredness to reality centeredness is taking place. These traditions are accordingly to be regarded as alternative soteriological ‘spaces’ within which or ‘ways’ along with, men and women can find salvation/liberation/ultimate fulfilment.[ John Hick, An Interpretation of Religion: Human Responses to the Transcendent (New Heaven: Yale University Press, 1989) ]

The hypothesis explains the weaknesses of any single religion to fully comprehend and capture the embodied idea of the Real (God). The reason being that God whom he called Transcendental Real is beyond human conceptuality, but rather, variously experienced and revealed in the comprehensive whole of world religions.

Hick’s hypothesis, is dependent on his inclination to Kantian distinction of the Noumenon Real and Phenomenon. For Kant, the mind only comprehends and interprets data of sensory experience and therefore, explains everything as they appear.

Thus, the Noumenon Real is contrasted from the Phenomenal. For the former, it is unknowable, for it cannot be known as it is in itself while the latter is within the reach of the human mind.[ Immanuel Kant, The Critique of Pure Reason transl. by Norman Kemp Smith (New York: St. Martin Press, 19650:173]

Finding this distinction convincing, Hick believes that, God is unknowable to one religion. This conclusion led Hick to reinterprete the historical Jesus, so to make room for his pluralistic campaign, to this now we must turn.

Hick’s Reinterpretation of the Historical Jesus

John Hick’s reinterpretation of the historical Jesus is one among many liberal and critical attempts to rediscover the real Jesus of history. As it will be demonstrated, there is a risen desire among biblical scholars (most especially of the New Testament) to unravel what was the real identity of Jesus of Nazareth. Against popular belief of the Jesus of history and Christ of faith, Hick advanced a theology of Christ that would appeal to other world faiths. This is so, for the church has traditionally held that, the fullness of God is made known in Jesus Christ and therefore, the Christian faith becomes the only unique, superior, final and nominative religion hence, it was founded by God himself.

In response to this problem of uniqueness, Hick devoted his later publications on appropriating the place of Jesus in History.

Hick’s starting point is to take seriously the New Testament data, and investigate its historical accuracy, (the Gospels in particular) and trustworthiness. For him, “the identifiable consensus begins with a distinction between the historical Jesus of Nazareth and the post development of the Church’s mingled memories and interpretations of him.” Hick insists that, the New Testament documents contain the mingled memories of first-hand accounts that have been preserved, winnowed, developed, distorted, magnified, and overlaid through the interplay of many factors,”[ John Hick, The Metaphor of God Incarnated Christology in a Pluralistic Age (London: SCM Press, 1993):9] and therefore unreliable. Since Hick feels that, the New Testament document does not contain accurate account of the historical Jesus, he proposes a new approach to that end.

Hence, the New Testament is a product of memories, he proposed a formula at which we can rediscover the real figure of the Church’s devotion. For him the formula is “imagination”. According to him “imagine is the right word, even though it must be imagination under the broad control of historical evidence”.[ Ibid] This imagination oriented in our mental pictures of the historical Jesus would help to arriving at who Jesus really was, what really did he think of himself on the streets of Ancient Palestine. Granting that formula, Hick concluded that, what can be known about the Jesus of history:

Jesus was a Galilean Jew, son of a woman called Mary; that he was baptised by John the Baptist; that he preached and healed and exorcized; that he called disciples and spoke of there being twelve; that he largely confined his activity to Israel; that he was crucified outside Jerusalem by the Roman authorities; and that after his death the followers continued as an identifiable movement. Beyond this an unavoidable element of conjectural interpretation goes into our mental pictures of Jesus.

Following this conclusion, Hick rejects all notions of supernaturalism in historical Jesus. The doctrine of virgin birth, walking on waters, empty tomb account of his resurrection were seen as a mere expression of the early Church’s theological and apologetically responses. Hick thought that none of these were claimed by Jesus about himself. He did not teach that he was the son of God, the second person of the Holy Trinity. Believing that the New Testament writers were not historically accurate, he went on to reject the Chalcedonian and Nicaean creeds hence, they were from the New Testament.

His rejection of the reliability and accuracy of the New Testament led him in suggesting a new look at Jesus of history.

The goal of that “reconstruction is to produce a Christology that is global and encompasses all religions. In doing this, there are two books that stand out; the Myth of God Incarnate e.d. by John Hick and the Myth of Christian Uniqueness e.d. by Paul F. Knitter and John Hick. The imploration of ‘Myth’ in both title of the books cannot be said to be misleading; their contents, materials and even the authors reflect the title. For better clarification of the term Knitter has something to explain; “we are calling ‘Christian Uniqueness’ a myth not because we think that talk of the uniqueness of Christianity is purely and simply false, and so to be discarded.”[ Paul F. Knitter, The Myth of Christian Uniqueness: Towards a Pluralistic Theology of Religions e.d by Paul F. Knitter and John Hick (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1992): vii] The articles in these books are proposed for a new Christology of which John Hick is the chief vocal.

Writing from a historical- cultural perspective, Hick developed a Christology of Incarnation, were Christ is seen as one among many of God’s incarnation. He acknowledges that, ‘‘God was incarnated in Christ as he was incarnated in Gandhi, Mohammed, Moses, Confucius and so on’’. Gandhi was inspiring for the Indians, so is Mohammed to Muslims and Moses to the Jews each calling for a proper respond to God’s revelation. Thus, Jesus of Nazareth should be understood in a similar manner.

For Hick, Jesus Christ was conscious of divine presence.

According to him the kind of Christ the Church should preach is one that “was intensely conscious of God as the heavenly father, his life, being dedicated to proclaiming the imminent coming of God’s kingdom to manifest its power in acts of healing, and to teaching others how to live so as to become part of the kingdom was presently being established”. [ John Hick, “Non Absoluteness of Christianity” in Ibid] Following this conviction, Hick posits that “the real point of and value of the incarnational doctrine is not indicative but expressive not to assert a metaphysical fact but to express a valuation and evoke an attitude”. [ John Hick, The Myth of God Incarnate (London: SCM Press)]

Hick suggests a metaphorical interpretation of all these traditional ascriptions to the man of Nazareth. It is these suggestions that call for a consideration of an inspirational Christology coheres better with some ways of understanding Trinitarian language than with others”.[ S. Nah, p. ] So for him, that Jesus was God, the son incarnate is not literally true, since it has no literal meaning.

A Critique of Hick’s Pluralistic Christology

The Christology reconstructed by Hick and his pluralistic colleagues is an outright denial and subjection of the New Testament account. This in turn attempts to deny Christianity her uniqueness. In this section the paper will attempt to give a response to Hick.

Firstly, Hick’s methodology is questionable. As noted earlier, Hick suggests the use of ‘imagination’ as an appropriate method to rediscover the real Jesus of History.

This imaginative contemplation is solely dependent on our mental pictures of Jesus. Relying on this methodology as the only possible method, would lead one in having a Jesus never taught by the New Testament writers. S. Nah has the following to say “such a procedure, accompanied by his imaginative approach to historical reconstruction, seems to cast serious doubts on Hick’s methodology as a whole”. How can we base our knowledge of Jesus of history on mental pictures? Would we not end up having one Biblical Jesus but many imaginative and mental pictures of Jesus? Throughout his thesis, Hick fails to account for these demanding questions.

One crucial aspect of Hick’s historical Jesus is the denial of the New Testament as a reliable source of History. More important was his claims that, the New Testament does not teach that Jesus is the Son of God, the second Person of the Trinity. This claim too is faulty and unreliable. Taking seriously the New Testament data, one will attest that Jesus of Nazareth enjoys a special position in human history, accordingly, Okwuosa, Nwaoga and Uroko charged that “Hick’s method for arriving at this conclusion is grossly erroneous and manipulative, in the sense that, he employed negative ecclectism in his choice of materials for this thesis.

He was literally at war with the sacred scripture, which he considered more or less a piece of literally work than a ‘faith- built’ source”[ Lawrence Okwuosa, et al “A Critique of John Hick’s Multiple Incarnation Theology and Christian Approach to Religion Dialogue” in Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5:8 (September 2017): 164]. One can also charge that Hick’s rejection of the New Testament accuracy is selective. The reason for this is that, his methodology would not allow him to accept what is contained in the New Testament. According to Anderson his use of the Bible is cavalier and notes that he freely ignores materials inconsistent with his conclusions’’[ N. Anderson, The Mystery of the Incarnation (Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1978):678]. In a similar way J. Dupuis insists that ‘’the real Jesus of history as critical exegesis is able to discover him today through the Gospel tradition, had done and said enough to warrant the faith interpretation of his person which in the light of Easter experience the apostolic church built’’[ J. Dupuis, Who do You Say I Am? Introduction to Christology (Marynoll: Orbis Books, 1994): 70 ]. There are notable names that accepts the reliability of the New Testament among honest and reputable biblical scholars. Names as F. F. Bruce, D. A. Carson, Raymond Brown, J. N. Sanders, C.K. Barret, Leon Morris among others. Hick’s rejection of such was not a product of sound biblical exegesis or thorough historical investigation but a mere display of linguistic dexterity grounded in Analytic Philosophy.

But the question is, what can one say about Hick’s claims that Jesus did not teach he was neither God nor his Son? Here, he needed to be reminded of Jesus claims in the fourth Gospel and the entire New Testament. One can only reject the divine claims of Jesus by himself by ignoring the implications of such claims.

While each of the Gospels writers had their specific purposes of writing, they were however, not reluctant to reveal the divine nature of Jesus of Nazareth. There claims made by Jesus that were only for God. For instance, he forgave sins, he calls for belief in him, he claimed to have come from above and seen end received from God. All these like other specific claims and Christological implied divinity beyond the formulations of Nicene and Chalcedon creeds.

There is now a growing awareness of the continuity of the Jesus of history and Christ faith. As indicated earlier Hick was insistent that the two are to be understood separately. That Jesus of history was an ordinary man who was conscious of divine presence, while the Christ of faith was the Church’s theological and doctrinal efforts to defend its cause. Such a thesis is untenable giving that the possibility of the Christian faith is made only possible with the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Interestingly Jon Sobrino, S.J notes the following, ‘’Jesus resurrection made faith in Jesus possible… the Christ of faith is none other Jesus of Nazareth’’.[ Jon Sobrino, S. J., Christology at the Crossroads, (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1984): 381] It is well indicated that, even the early disciples lost credibility in accepting Jesus’ resurrection until he asserts to them he was. For instance, Thomas was resistant to accepting the resurrection story until he had an encounter, an encounter presented by sound evidence.

Conclusion/Recommendation

Hick’s reinterpretation of the historical Jesus and clear distinction of him from the Christ of faith was motivated from his awareness of the manyness of traditions, ethics, and religions. This is so, to allow the inclusion of other faiths. But as noted earlier, the New Testament account is a reliable first document to provide a flawless and trustworthy story of the Jesus of History. The post Easter Christ of Hick is in every way in sharp dis-agreement with what the New Testament writers understood him to be.

Though we live in a pluralistic society, such awareness should not create room for the rejection of the New Testament and the uniqueness of Jesus Christ, and therefore, the following are recommended:

-It should be encouraged that, Christian Biblicists needs to rise to the challenges of the modern world.

This includes the challenge of religious pluralism and their reconstruction of the historical Jesus. This project of the pluralists seeks to destroy the foundation of the Christian faith. Christians needs to engage into honest historical search of the biblical account guided by sound exegesis. The fruits of this task will be of benefit in appropriating the message of the Church in a pluralistic society.

-While maintaining uniqueness, Christians are encouraged to embrace other faiths with love. Allow room for religious dialogue mutual discussions and tolerance. While doing this, they should present Jesus Christ as the revealer of God and mediator between man and God.

Bibliography:

Comments

Post a Comment